I recently undertook a study of Käthe Kollwitz, a German printmaker, sculptor, and graphic artist. Born in 1867, she grew up in a leftist home where her parents were socialists. Their political activism instilled in her a lifelong concern for the rights and freedom of all humankind. She especially had a heart for the powerless and oppressed. She used her artistic gifts to draw attention to social problems and to lobby for antiwar and anti-fascist positions.

I was particularly drawn to the seven woodcut prints that she made in response to World War I and released as a series called War. She began working on sketches in 1918 and spent several years experimenting first with her preferred medium of etchings, then trying lithography, and finally settling on woodcuts. Her struggle to find the most appropriate medium seemed to mirror the terrible struggle that the war years had brought to her life. This war series represented a change in her personal stance about war, how in the early days of World War I she believed the war was justified but then changed her mind, becoming a pacifist and an advocate for the end of all wars.

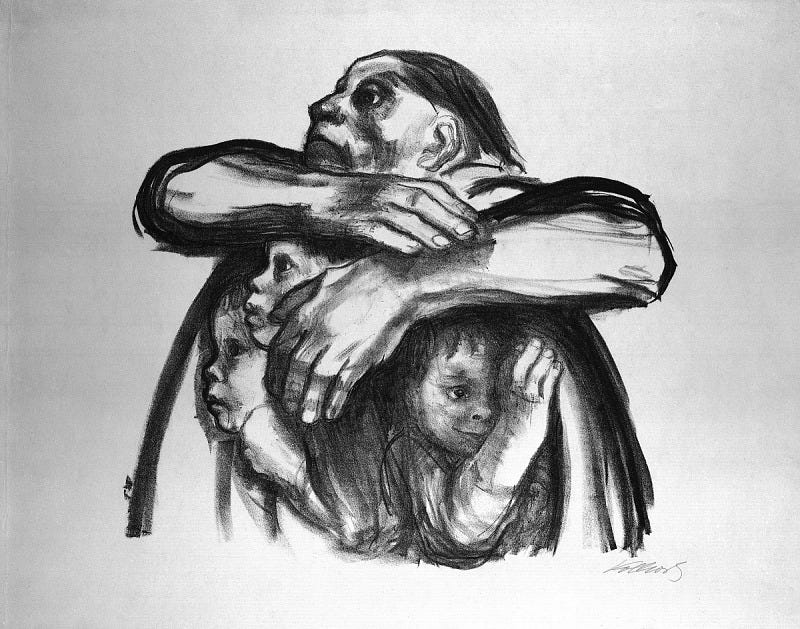

In this series, she shows us the hideous price of violence in terms of those who are left behind to bear the suffering, such as mothers, widows, and children. Only one of the prints in the series, The Volunteers, shows the combatants, including her son Peter, who she depicts standing next to Death. He was one of the early casualties, killed in October 1914.

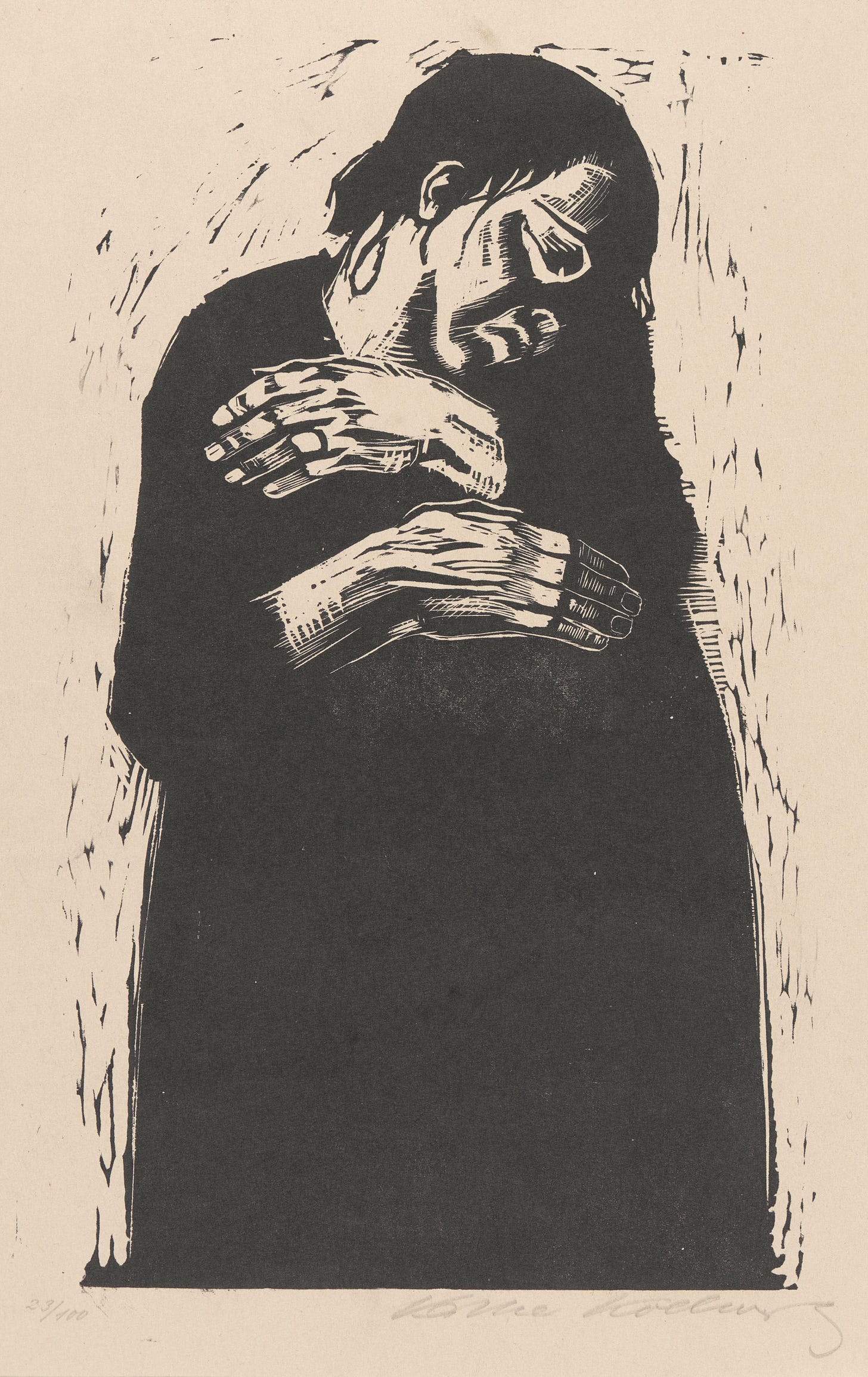

More than any print in the series, I focused on The Widow. In The Widow, a woman is left alone with her fears and grief. She hugs herself trying to bring solace to her unborn child. Her face shows the anguish of grief; her tilted head indicates vulnerability and powerlessness. Kollwitz used Japan paper to print this woodcut, which is a high quality paper favored by a lot of printmakers because it absorbs ink well and allows for that saturated, velvety black hue. I think the stark black and white nature of a woodcut mirrors the heaviness of grief. The contrasting value of the black dress focuses our eyes up to the woman’s disproportionally large hands and her heavily gouged face. Both have a skeletal look to them, like bone and sinew, that I interpret as a symbol for death.

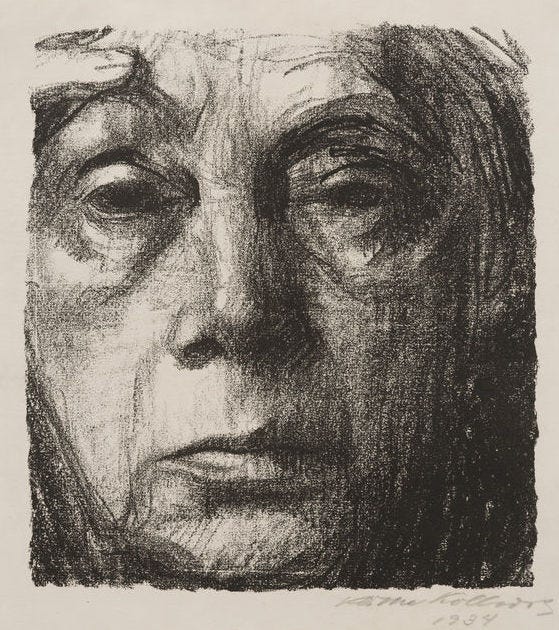

Kollwitz was known for having created hundreds of self-portraits. In this crayon lithograph from 1934, we see a woman who thinks and feels deeply, a woman who has known tremendous sorrow.

Yet, this is a portrait of someone who doesn’t know that she will have to endure another world war that will rob her of even more, including a grandson.

Because of Kollwitz’s political leanings, the Nazis fired her from her teaching post and labeled her works as “degenerate,” which banned her from being able to exhibit them. She continued to work in secret and created a final print cycle titled Death that was a metaphor for what she felt had become of her country.

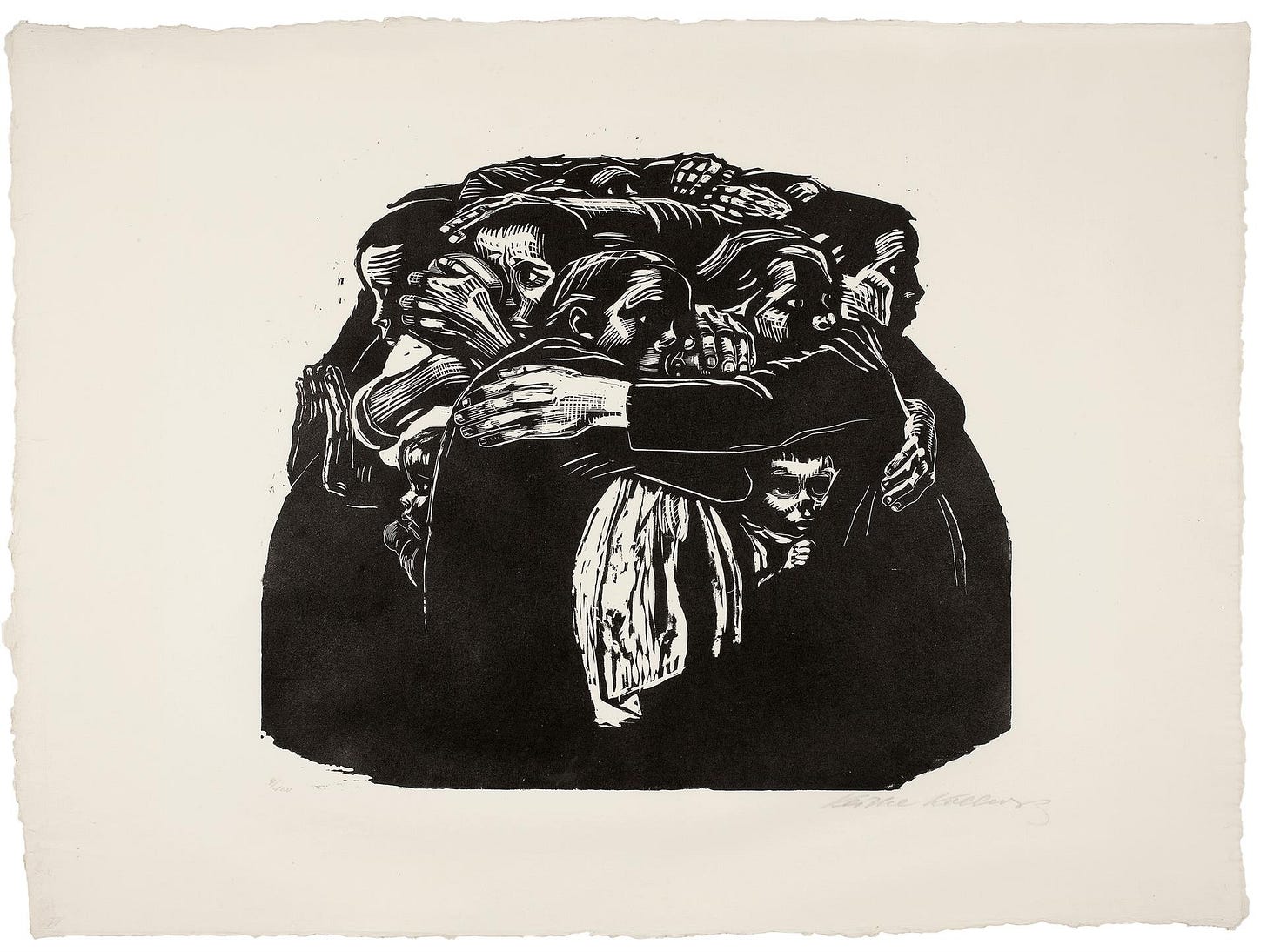

In December 1943, Kollwitz wrote in her diary about what would be her final piece, Seed for Sowing Should Not Be Milled. It was a phrase quoted from Goethe that she had originally used in 1919 as part of an open antiwar letter. Kollwitz again feels an obligation, a desperation, to prove there is no romanticism in war. She used the medium that she knew to protest the Nazi recruitment of children for the army.

This is now my legacy: “Seed for sowing should not be milled.”…So I painted the same scene again: Boys, proper Berlin boys, who greedily scent the air outside like young horses, are held back by a woman. The woman (an old woman) has wrapped the boys into her protective mantle, spreading her arms and hands over them in a violent and dominant gesture. “Seeds for sowing must not be ground” – this demand is, like “Never again War,” not a sentimental yearning, but a command, a demand. (Kollwitz Diary, December 1943)

The lithographic stone for this final print and much of her other work was destroyed in the 1943 Berlin bombings that also claimed her home. Kollwitz died on April 22, 1945, a mere eight days before Hitler’s suicide and two weeks before Germany’s unconditional surrender that ended the war in Europe.

Kollwitz had a unique ability to depict suffering. Her work is not easy to look at, but I think it touches us deeply. The images stay with us, haunt us. They echo like a challenge to us today. Will we speak out against violence, hate, and injustice? Will we protect the vulnerable? Or will we be complicit in our silence and apathy?

A powerful story, beautifully written.

Thank you for continuing to share your insights with your awesome prose.

Wonderful piece. Thank you.